How one therapeutic community with a unique approach to accountability is breaking the cycle of incarceration, addiction, and violence

The Bench

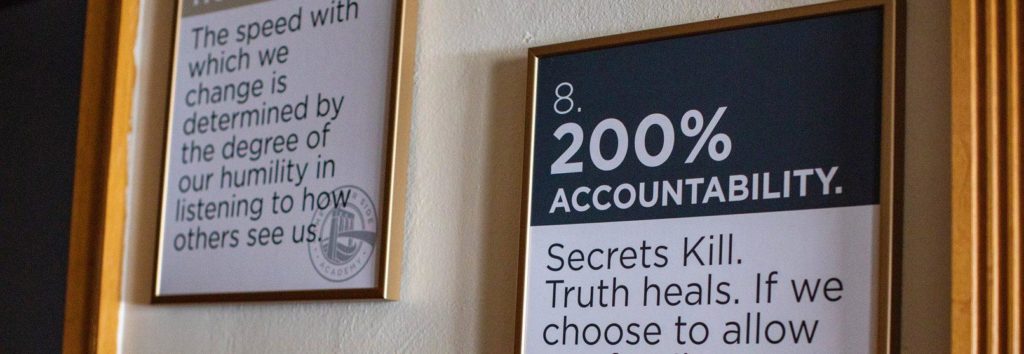

She waits on the bench radiating anxious energy with hair pulled back, head bowed, hands clasped, ankles crossed. She looks up occasionally, glancing at the framed statements hung around the room: #2 Make and keep promises. We can’t simply change our address; we must change ourselves. #7 Each one teach one. When A teaches B, A gets better. You can’t keep it without giving it away.

The room is busy with people working, answering phones, coming in and going out, but no one speaks to her and she speaks to no one.

It’s a plain bench, no decoration. And it’s rock bottom—the starting place for everyone at The Other Side Academy (TOSA). There are no guards here, no ankle monitors, no handcuffs. It’s entirely her choice whether she stays or goes. Peers who have been where she’s been are ready and waiting to help her, if she’s serious.

A potential student can apply from jail or walk in off the street, but upon arrival at the home, everyone starts out on the bench. Eventually a staff person will explain a bit about the program and let her know she’ll be on the bench for a while before she’s interviewed, giving her a chance to think about why she’s come, where she’s been, and if she’s ready for this.

For Master Student Ashlee Unden, who has now completed the program but chosen to stay involved, the bench was a defining moment: “Sitting on the bench seeing everyone so happy, seeing people from my past who had become so different made me want to make the commitment to experience that same change.”

After time on the bench, the interview begins. And this is when things can get hairy. The applicant tells their story and sometimes it’s necessary for the staff person conducting the interview to turns around and throw the facts of the story back at them, pointing out all the mistakes they’ve made, people they’ve hurt and disappointed, the mess they’ve made of their life. If that person can sit there and take it, without flying into a rage or becoming defensive, they’ll be welcomed and soon surrounded by a peer community that becomes core strength and accountability through the long, deep process of change.

Ashlee got heavily involved with drugs in high school. And then pregnant. Not fit to be a mom, her daughter was adopted by her parents. Dave Durocher, TOSA’s Managing Director in Salt Lake City, was the one to interview her. “Dave just lit into me and told me what a horrible mother I was and what a horrible person I was and how much havoc I’ve caused on the world and all of these things. And he was right,” said Ashlee, “But no one’s ever told me that before. For whatever reason, I don’t know why, the raw feedback like that, people seem to gravitate towards it.”

“The interview process is extremely important. We’re going to give you some emotional punches to the belly because we want to see if you can own who you’ve been,” explains Dave. “If you can own that, then maybe—only maybe—you can change.”

This isn’t for everyone. The Academy is for the “absolutely completely broken,” says Dave. “The piece of the population that has cycled through the system over and over again, the piece of the population that doesn’t do well in the typical program.” The average student has been arrested 25 times, he says. “We have to dig in and help them change those behaviors. Learning to make good choices is really hard when you’ve been habitually making wrong choices for decades.”

The average TOSA student has been arrested 25 times.

After a person is accepted to the program, they hand over everything that represents their previous life. Mohawk? Shaved. Piercings? Out. Facial tattoos? Removed. Makeup? Washed off. Excuses for the choices that got her to this point? Swallowed. These are the first steps of taking responsibility.

Now out of the interview, the woman from the bench gets a new outfit, quite a bit more modest than she’s used to. From this point forward, she is moving toward a new future and any reminder of her past is discarded. Then, humbled and sincere in her commitment, she’s ready to begin the hardest challenge of her life.

If she can endure, she will shed her old life and unhealthy habits and will emerge on the other side entirely transformed, no longer resembling the person on the bench.

The Cure for Cancer

TOSA’s program is based on the Delancey Street model, a therapeutic community that started in San Francisco in 1971. Delancey Street has replicated itself a few times in its nearly 50-year history, the last time in New Mexico. Its six campuses are still going strong, but it has stopped spreading to different cities.

Social scientist and New York Times bestselling author Joseph Grenny (now chairman of the TOSA board) and start-up guru Tim Stay (now CEO) learned about Delancey Street and were so impressed with the program—and baffled by its failure to expand beyond a few locations—that they teamed up to start The Other Side Academy in Salt Lake City. They knew they needed people familiar with the culture of Delancey Street to start their academy, so they reached out to Delancey Street graduates Dave Durocher and Lola Strong and invited them to Salt Lake City to be part of the launch. For both, it was an easy yes.

“It’s the only thing that really makes sense of everything that I chose to do for as long as I chose to do it,” says Lola, who spent 20 years as a heroin addict after getting addicted to pain meds following a medical procedure as a teenager. “I shouldn’t be alive because of the choices that I made. For some reason, my life was spared. Being offered this opportunity and getting to do this, getting to be a part of something like The Other Side Academy, makes sense of everything.”

Similarly, after decades of dealing drugs and with a 22-year prison sentence hanging over his head, Dave got a chance at Delancey Street, where he ended up staying eight years—the first three as a student and the last five managing the LA facility. After he left, he worked construction and then found himself on the oil fields of North Dakota. He was more than paying the bills when the invitation to TOSA came. “I realized making money was fun, but changing lives was rewarding.”

Dave and Lola are both so passionate about the success of the program that they want to spread it to every city that wants it. “When you’ve found the cure for cancer, you can’t keep it to yourself,” says Lola. Just four years after they started they were discussing expansion, and that’s when Denver came calling.

Colorado’s state system includes 43 county jails, 20 state prisons, 3 private state prisons, and 4 federal prisons. World Prison Brief’s 2018 data shows that if Colorado were a country, it’s incarceration rate of 635 would rank the state second in the world. The United States as a whole is ranked first at 655, with El Salvador in third at 604.

If Colorado were a country, its incarceration rate would rank second highest in the world, right behind the United States.

Business leader Andrew Schmidt was part of a 2016 Denver delegation visiting Salt Lake City researching solutions to common social problems. The group was impressed with TOSA. When Mayor Michael Hancock asked for a citizen volunteer to spearhead an expansion, Andrew raised his hand. “I think I blacked-out, actually,” he jokes. But he was serious about getting the program to his city. “It’s about bringing dignity back to a population that much of our community has given up on. This model works, is self-sufficient, and breaks the systemic cycle of homelessness, addiction, and crime that repeats itself over and over again.”

Andrew admits he made plenty of mistakes in his youth, he was just lucky enough never to get caught. “I should’ve been in those shoes, but I’m not,” he says. “So what am I doing to move this needle in their lives? Our Leadership Foundation Community can get this done, and I feel like I was meant to lead it.”

“Denver is one of the fastest growing cities in the country,” says Anthony Graves, Director of External Affairs for Economic Development for the City of Denver. “As the city grows, all populations grow with it,” even the ones having difficulty, he means. “We’re trying to expand our portfolio of credible partners that have a care model that is effective and invaluable to our city government. We believe TOSA is a great model in this space and will be a great complement to other city partners.”

To bring TOSA to Denver, Andrew formed an advisory council to raise $2.8 million for the purchase of a property and operation costs for the first two years. While the Academy is renting space for a year until their new home is ready to sleep its ideal 150, the bench has already been a bedrock moment for a couple dozen students.

200 Percent Accountability

It’s an intense two-year, peer-driven journey during which students work hard at assigned tasks and learn to listen to feedback about their unhealthy character qualities with grace and humility.

Students who successfully complete this program learn to change bad habits by internalizing twelve core beliefs, which the founding Salt Lake City team defined together years ago. “We started thinking about what we wanted a successful graduate to look like,” Lola explains. Their goal went beyond simply keeping people employed and out of jail to people able to live with integrity.

One of those beliefs is “200 percent accountability. Secrets kill. Truth heals. If we choose to allow our family to become ‘dirty’ we kill the very thing that will save us.”

“It’s not a drug treatment program—it’s an accountability program,” says Tim. “The point is to be held intensely accountable for long enough that you become a new person. In prison, the last thing you want to do is call someone out for something, or report someone to authority. If you do, you’ll suffer for it. In TOSA culture, we’ve changed that. Allowing someone to continue in their destructive behavior is allowing them to put their lives at risk. If we care about this person, we’re going to call them on their behavior, and if we want to change, we’re going to allow others to call us on our behavior. I’m 100 percent accountable for myself and I’m 100 percent accountable for my peers—that’s 200 percent accountability. Because we’re willing to care about others, we’re willing to hold them accountable.”

What does that 200 percent accountability look like? Feedback—also called a “pull-up”—immediately and about every unacceptable action.

There are no therapists or counselors here; everyone has a past, so everyone has credibility and can point out when a fellow student has acted out of line. Late? Expect a pull-up. Cat-call a fellow student? Pull-up. Have a bad attitude? Pull-up. Brag about an accomplishment? Pull-up.

200% accountability is doing what they’re told without getting angry about it, even when the task feels beneath them, like cleaning the bathroom for the fifth time. But it’s also airing grievances at the twice-weekly “games”—a group gathering when a student can say how he or she really feels about a reprimand.

And when a student violates any of the twelve beliefs, 200 percent accountability is accepting the consequences, which come in the form of hours and contracts. “Hours” are simply extra chores done in 60-minute periods outside the regular work day. A student on contract, however, does only chores for days, and sometimes weeks, from 6 am to 10 pm. When on contract he is set apart from his peers with a yellow t-shirt. He can’t talk to anyone unless he’s asked why he’s on contract (which peers are expected to inquire about to show they care).

Students can get multiple contracts without being expelled from the program. But no one can violate belief #10: Boundaries. We will not commit any act of violence, make any threats of violence, engage in any substance abuse, become a threat to our community. If a student is found guilty of any of those, he is kicked out of the house, no exceptions. If he returns and is truly repentant, he might be given another chance, but there’s no guarantee.

Finally, 200 percent accountability is pulling up a peer trying to relive their “glory days.” During the first fifteen months, students aren’t allowed to talk about their past. “Most of our students are dealing with disconnection,” Tim explains. “The way they’ve learned to connect is by building a false facade about who they are and creating a false pride about what they’ve done. In previous programs, or in jail, the way you get your reputation is by talking about all the terrible horrible things you’ve done, that’s how you get your status. But there’s nothing there to be proud about, there’s nothing to say this is something worthwhile.”

“When you’re fresh and you’re brand new, you see your past as almost glorious,” Ashlee explains. “So not talking about it for that long and really working on yourself, you start to see it through a different lens.”

With that major topic forbidden, students need to learn anew how to have a conversation. Every day after lunch, they participate in “Seminar”, a half-hour session when everyone who’s at home gets an opportunity to practice speaking in front of people. Every seminar has a theme. For example, Sunday evenings they watch 60 Minutes as a group and then at Monday’s Seminar they discuss what they heard. Every day a different student facilitates, standing up to face everyone and going over the rules: No hands in pockets, no staring out the window, no profanity. They’ll share their thoughts about the topic, and then call on volunteers to share. In this way, students gain experience formulating articulate thoughts, speaking respectfully in front of groups, and listening with full attention to their peers—all valuable life skills they will need when they graduate the program and reintegrate into society.

“The whole point of a therapeutic community is to get the person to experience whole person change,” says Dave. “If they learn to tell the truth impeccably, if they learn to be accountable 100 percent of the time—the sum of those two things is integrity.”

“If you’ve got integrity, nothing else matters. And if you don’t have integrity, nothing else matters.”

Dave Durocher, Managing Director, TOSA Salt Lake City

Moving Forward

As a self-sustaining enterprise, TOSA does not receive government funding. Through their moving company and in Salt Lake City their thrift boutique, they cover all their own costs. “We don’t want government funding,” says Lola.

“We don’t want to rely on anybody anymore. We’ve been relying on the government when we’ve been incarcerated. We’ve been relying on stealing from people. We’ve been relying on our parents. We haven’t taken care of ourselves ever. We want to take care of ourselves now. That does something to us that makes us whole again. That’s what leads to the success of our model and our students.”

To sustainably pay the bills and employ their students, TOSA started a moving company—The Other Side Movers—whose tagline is “rebuilding our lives by moving yours.” As Dave likes to say, “Turns out we’re pretty good at moving your valuables, but this time, with your permission.”

You might think clients would be skeptical about having ex-felons move their stuff, but the Yelp reviews suggest otherwise: Mostly 5-star reviews detailing punctuality, friendliness, and great care in moving large items. And when clients learn about the academy’s story, they’re even more inclined to support it. In fact, the thrift boutique got started when people who were moving offered to donate items they didn’t want to take with them. The moving company collected so much furniture and sundry other items, TOSA started selling it.

In Salt Lake City, the moving company generates about $2 million a year.

TOSA works a bit like a university in that students start as freshmen and progress every few months to the next level—sophomore, junior, senior—all typically achieved within the first year. Freshman are tasked solely with maintaining the grounds, while sophomores get called to various jobs—the moving company one of them.

Justin Allen manages The Other Side Movers in Denver. He’s been with TOSA for nearly four years now, having spent his previous 20 years caught in the revolving door of drugs, addiction, homelessness, crime, and jail.

“The moving company teaches students how to work with each other, how to provide good customer service, how to be accountable, because there’s things that happen on moves that we like to be accountable for,” explains Justin. “Any tiny minuscule scrape or a scratch or ding in the wall, we hold ourselves accountable to that. And that’s what sets us apart from a lot of different companies. My mindset has been we have a lot more to prove and a lot more to lose than other people.”

My mindset has been we have a lot more to prove and a lot more to lose than other people.

As with everything, there are rules for the movers: Alert the crew boss to the presence of any prescription drugs, who will ask the client to remove them, to create a safe place for the students and eliminate temptation; no profanity; and no arguing about tasks, just do as you’re told.

In Salt Lake City, the moving company generates about $2 million a year. “Here in Denver, we’re so brand new and we only have one truck with a skeleton crew, but we have surpassed our goal every month,” Justin says. “Not by much, but enough—enough to feel good about it.”

Students don’t receive money working for the moving company (although at fifteen months they do start earning “WAM”—walking around money), but they learn work ethic and gain something even more valuable at this stage of their journey—purpose. “Idle hands will get you in trouble,” Justin says as he smirks knowingly. “If you don’t have something to do, if you don’t have a purpose, then a lot of us revert back to what’s comfortable.”

“We want to take care of ourselves now. That does something to us that makes us whole again.

Lola Strong, Managing Director, TOSA Denver

The Bridge

Students that make it through the full two years commemorate their achievement with a special graduation ceremony, crossing a bridge as they recite the twelve beliefs, which by now are second nature. This is the second time they cross the bridge, actually.

Early on, the leaders found that people were leaving within the first two weeks, so they created a milestone to allow students the opportunity to declare their intent to complete the program after an initial period of observation. “If they chose to be a part and become freshmen, then they would cross the bridge. When they crossed the bridge, they would make commitments, and because they were deciding, that made people stay,” says Lola.

57 percent of students who cross the bridge the first time end up crossing it a second time, and of the 48 that have graduated so far from Salt Lake City, 45 are employed and remain free of the snares of that vicious drug-crime-jail cycle.

To bridge the gap between the restrictive safety of the academy and the harsher realities of the outside world, TOSA offers graduate housing where students can live for $100 a week for up to a year after completing the program. “In Salt Lake, we found that a lot of the students were going out and filling out applications for apartments, and because of their felonies, they were being denied,” explains Lola. Twelve months of solid rental history helps clear that obstacle with a future landlord.

But many people end up staying at the academy beyond the two years. People like Ashlee and Justin, who were both invited to come from Salt Lake City to help launch TOSA Denver, people who before their time at TOSA got high off drugs and alcohol, but who now “get high” off helping people who are struggling with the same issues they’ve successfully overcome.

“The best part about living here is just being a part of something bigger than yourself,” says Ashlee.

“I never thought in a million years me being in that cycle of that revolving door of in and out of jail and prison for so long, I never thought in a million years that I would be in the position I am today.”

Ashlee Unden, Senior Leader