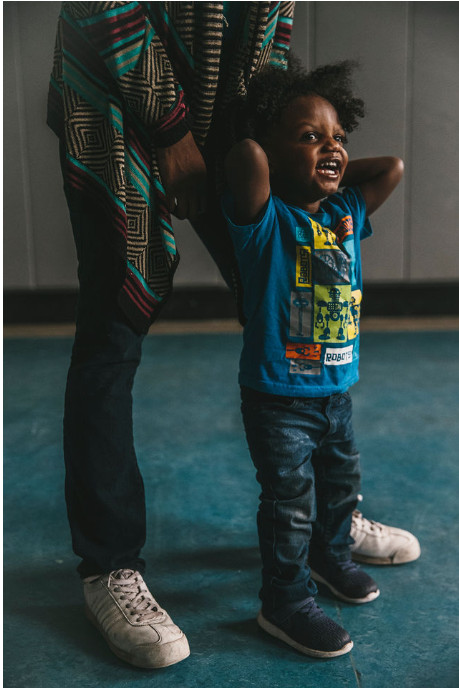

Surrounding families in crisis with compassionate community

Families on the edge

Parents encounter struggles every day. For those with support, these challenges are mere blips in their life journeys — events to be recounted with gratitude for having made it through. But for the hundreds of thousands of families without any support, these challenges can often push loving parents right to the edge, even putting them at risk of losing custody of their kids.

Just before this proverbial edge, where children are at risk of entering the foster care system, Safe Families creates another path, meeting vulnerable families with compassionate community that provides support for parents and safe care for their children.

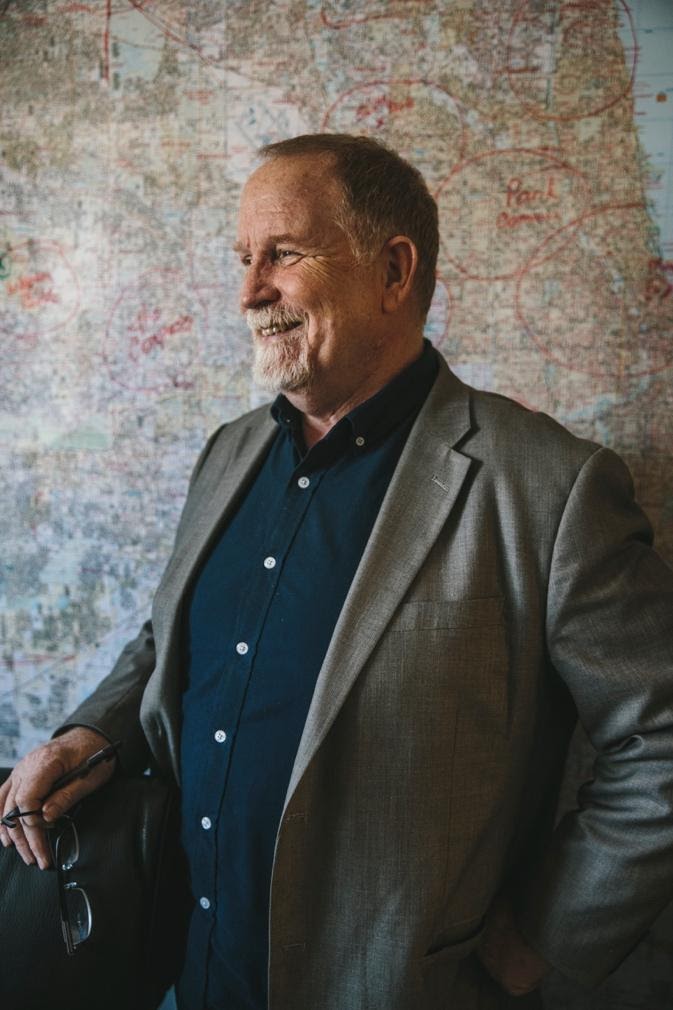

It started 16 years ago when a family psychologist, Dr. David Anderson, met a young girl in especially bad shape: broken arm, detached retina, black-and-blue face. She could barely speak. Dr. Anderson needed her to talk so he could provide care, but the child, only five-years-old, had been traumatized into speechlessness.

As he brought his questions to the sweet girl’s mother, an intervention began to form in his mind’s eye. Mom had needed someone to watch her daughter while she worked. Having stayed home with her a couple days because of illness, Mom was in danger of losing her job if she missed another day.

This mother had no support. She had grown up in foster care and aged out without a forever family, so in a moment of desperation, she reached out to an ex-boyfriend for child care. He abused the little girl.

Dr. Anderson had a daughter around the same age, so he was particularly outraged by the situation — yet another casualty of the state’s flawed system, which offers only reactive investigation, not proactive or preventive support. He wondered, “Why do parents harm their kids or put them in unsafe situations? And why, as a culture, a system, a state, do we wait for kids to be harmed before we’re willing to help them?”

The latest research revealed that social isolation was believed to be a key factor in child abuse: Parents lack a support system, they fall on hard times, the stress is too much, and the kids end up in unsafe situations. Unfortunately, usually in cases of abuse, by the time the state gets involved the kids have already experienced trauma from unsafe or unstable home environments. In cases of neglect, which includes about 70 percent of the 443,000 kids in foster care in the United States, the foster care system often takes children from their parents because the parents don’t have other options. More often than not, they love and care for their children and aren’t physically hurting them — they just need help to get through a difficult patch, like homelessness, addiction, illness, or unemployment.

Dr. Anderson wondered: Would it be possible for neighbors, churches, and the community at large to step up and come alongside these families when life first gets overwhelming? Can we provide them with the support and extended family they need before their children are put in a worse situation?

And that’s how Safe Families began: a foster care preventive, where children are placed in a supportive environment and temporarily cared for by host families as their parents get the help and support they need to endure difficult times.

Engaging the city

Dr. Anderson penned a letter to the mayor of Chicago explaining his idea to recruit families to take care of kids whose parents are in crisis. The key factors: Hosting families would not be paid or have any expectation to adopt. Foster parents, Dr. Anderson explains, are getting money for a parent’s failure, and if that parent fails again, the foster parent is asked to adopt the kids. “And so there’s this barrier that exists between these two people. I knew if we could take money out of the equation … that parents [in crisis] would be much more amenable to help.” And host parents would know from the start that the kids would return home as soon as their parents were able to care for them, so adoption wouldn’t be a motivating factor and parents in crisis wouldn’t be wary that host families could take their kids away from them.

The mayor was skeptical — he didn’t believe families would take care of other people’s children without some sort of incentive. But his deputy chief of staff for human infrastructure, BJ Walker, understood the potential: “I saw it as playing a role of tapping into a resource that we hardly ever think of tapping into. We are always so focused, in human services, on who’s in trouble? What’s the problem? What’s going on that’s going to put people at risk of this or that? We forget to tap into the energy that’s available and families who are doing quite well and doing well enough that they have something to provide to others.”

So in 2003, with initial funding from the city, Dr. Anderson launched Safe Families for Children, a nonprofit that surrounds families in crisis with a compassionate community.

Informed by the model of radical hospitality in the Bible and Jesus’s command to love your neighbor, and believing that family can be the most powerful change agent in society, Dr. Anderson moved ahead with two audacious goals: “To change the world by intervening in the lives of these families before bad things happen, and to make the safety of children in our society all of our responsibilities, not just that of the public child welfare system.”

The impact since the earliest days has been astonishing: Safe Families has helped reduce the number of kids going into foster care from 52,000 to 15,000 in Illinois.

Amanda and Michael Vander Pluym were already foster parents when they heard about Safe Families through their church. Amanda had known of a family whose children were going into foster care because they were often left alone while the father worked. Amanda thought, “He doesn’t have a lot of help. To me it seems unfair that he’s doing his best and he’s trying to just support his family. And it didn’t seem like something that a kid should be removed from a family for.” Safe Families appealed to the couple because it allowed a family to step into a situation like that and keep the kids out of the state system, where potentially further damage could be done.

The Vander Pluyms have hosted several children through Safe Families over the last few years. Currently, they’re taking care of one-year-old Callum, who Amanda says spends his days climbing all over the coffee table. His mom, Kiasia, was struggling with postpartum depression when she was referred to Safe Families the first time. With no family around, she didn’t know where to turn. She loves her son and wanted to keep him, but she needed help while she recovered. Fortunately, a Safe Families host family near her was able to take care of her son while she healed. A few months later, she found herself homeless and reached out to Safe Families again for help. This time the Vander Pluyms were available. While Kiasia looked for housing, she was confident that Callum was is in safe hands, and she was able to visit him as often as she liked while she rebuilt her life.

Kiasia recently found housing and Amanda explains, “Because Safe Families isn’t foster care, and she’s a safe person to be with, he can go home anytime. He goes home on the weekends, and for the holidays and stuff, she had him.”

Dr. Anderson explains this is a fundamental difference between foster care and Safe Families. With foster care, parents have limited contact with their kids. With Safe Families, parents maintain their rights and can decide to have their child back with them whenever they feel they are ready. The host families are strongly encouraged to form a relationship with the placement parents and communicate regularly, with the goal that this relationship continues after kids go home.

“I grew up a son of a bricklayer, so I had no vision or idea of, ‘Oh, this could be huge.’ I was thinking, ‘Let’s just help a few people.’”

Dr. Anderson

In 16 years of supporting families in crisis, Safe Families has facilitated more than 50,000 hostings, placing 38,000 children in loving homes for however long a parent needs, which, on average, is 45 days.

Reimagining the village

Laura Linton and her kids, Matthew and Payton, were another family in crisis helped through Safe Families. Laura needed to go to rehab, and the program allowed her to bring her daughter but not her son. Her Department of Child and Family Services worker referred her to Safe Families, and Dr. Anderson and Karen were available to take in her son for the 120 days of the drug treatment program. Later, they took in both of her children so she could have spinal surgery, and they opened their home a third time when she had to heal from another surgery. “They’ve been there over and over for us,” Laura says.

Unlike with foster care, the relationship doesn’t end when the kids go back to live with their families. The Andersons have become extended family for Laura. They spend holidays together, and Laura often calls Karen when she needs advice about something.

“We talk a lot,” Laura says. “And I just feel comfortable because I didn’t have a mother there, and I’m not saying she’s my mother, but I kind of look to her like a mother figure, like somebody I feel comfortable asking a question, and they might not know, but they’ll send me in the right direction.”

Safe Families’ goal is to create that extended family for every family it helps. To ensure no host family is isolated, each one is surrounded by a Circle of Support: people vetted by Safe Families who provide goods and services and emotional support and ensure a hosting situation is beneficial for all involved.

Family Friends provide babysitting and meals, and Resource Friends provide goods and services like age appropriate toys, clothing, and funding for activities. Family Coaches, some of whom are paid staff but most of whom are volunteers like everyone else in the Circle of Support, check in with the host family within 48 hours of a placement to answer any questions and see if there are any problems, or if the host family needs anything. This person then checks in regularly with the host family, the children, and the placing parent. The coach also makes a plan with the placement parent to help them reach their goals so their children can return home to them. Finally, the coach debriefs with the host family post-placement to find out how the process went, understand what the host family would do differently next time, and determine if/when the host family is ready for another hosting.

Each person in the Circle of Support is thoroughly vetted and trained for their role, says Joyce Moffitt, director of the Greater Chicago Chapter of Safe Families for Children. And then these volunteers — 25,000 strong — are notified of relevant needs with requests coming from many sources: a parent calling on his or her own behalf, an agency worker; a Department of Child and Family Services, school, or hospital social worker; a police officer. Someone at a Safe Families intake office records the details of the situation and decides whether Safe Families can help.

“The type of kids we’re able to help is really contingent on the skills of the volunteers, their skills and interests,” says Joyce. Once, an infant needed hospice. A host mother who had worked as a neonatal nurse and had experience with hospice situations responded, willing to take the baby.

Joyce pulls out her phone, opens a thread, and scrolls through the requests. The latest is for an eight-year-old girl who needs a place to stay for a few weeks. It’s noted that she likes dolls and games.

“We call it disruptive generosity,” says Joyce, “so when we can bring in a Circle of Support around not only the mom that’s struggling, but the family that’s doing this, it’s amazing.”

The Circle of Support allows anyone to get involved at their own comfort level. Not everyone is able to host, but maybe they have a skill that would be helpful for a host or placing family. “It might be within a faith community or a Safe Family network that somebody is a dentist and they say, ‘I’m not going to host kids in my home, but for pro bono I would see a child,’” explains Joyce. This allows the community to use their skills and talents for good by helping people around them.

The final link in the Circle of Support is a Safe Families Church, which is a faith community that supports Safe Families as a ministry of their church. Any host family whose church isn’t officially part of Safe Families is connected to one that is, to have access to that support system. Safe Family Churches often have resource rooms to store donated items such as diapers and baby gear that volunteers can access when their host families need something.

“We have churches that will send a pizza the first night of a hosting. I mean, there’s all sorts of amazing creative things that our volunteers do.”

Joyce Moffatt

Overcoming barriers

Today Safe Families for Children operates 108 chapters across 70 cities in 40 states. Yet, it has not been an easy road. Safe Families has had to navigate complex systemic and legal challenges in every city and state where it has launched chapters.

COO Ken Norwood says he receives several calls a week from people interested in bringing Safe Families to their city. His team follows up with each one, coaching through any legislative barriers that might exist and ensuring they have support on the ground, not only with people ready to volunteer, but also partnering with necessary government stakeholders.

Wisconsin was the second state to host Safe Families. When a family in Milwaukee needed help, Safe Families was prepared to step in, as it had successfully done in Illinois. But the local Department of Children and Family Service declared Safe Families’ assistance illegal because the family needed to be under the jurisdiction of the state to receive the help they needed. Many states’ laws, Dr. Anderson explains, indicate that “anybody making connections with people is really doing placements, and placements need to be governed by the state. They never imagined that there would be people helping families who aren’t wards of the state.”

One mom, outraged by the notion that Safe Families was prohibited from helping this family, leapt into action to help. “She got all these other moms and they’d developed this massive movement of these moms that started calling the capitol, calling their state legislators,” says Dr. Anderson.

And then Safe Families got a lawmaker on its side. Wisconsin state Senator Dale Koyenga realized the obstacle could be removed with legislation. The Safe Families Act of 2011 allows Safe Families to file the necessary paperwork that gives host families the right to make decisions about the kids in their care. The state doesn’t need to be involved, and no one needs to set foot in court.

Ken did experience the cold shoulder when he tried to start the first chapter in Colorado (where there are now three flourishing chapters). “I think Colorado still maintains that wild west independence to it,” he explains. “We don’t like a lot of rules. We don’t like a lot of structure, so for [Safe Families] to come in and have something in hand … a beautiful holistic approach to the needs of children in crisis can be a threat.”

Ken received a cease and desist letter from the state when he tried to launch Safe Families in Colorado Springs. That’s when he learned about Milwaukee’s legislative efforts and began the process of getting the law replicated in Colorado.

This same legislation has been replicated nearly 20 times as chapters in different states have encountered similar resistance. And each state that has laws prohibiting the operation of Safe Families will need to enact similar legislation, notes Senator Koyenga, because issues involving children are usually left to individual states to deal with.

As they continue to do this necessary work on the legislative end, Safe Families has begun to see the long-term impact of its program on keeping kids out of foster care.

And it is seeing that downward trajectory that Dr. Anderson dreamed about from the beginning. In Chicago alone, Safe Families prevents nearly 1,000 kids from entering the child welfare system every year. And these compelling statistics are being noticed. Once skeptical of Safe Families, “the Wisconsin Department of Children and Family Services now wants to consider them a viable opportunity to build support for families,” said Nicole Zorn, Safe Families Wisconsin Director.

Such support is crucial. The state system needs to view Safe Families as one of the tools in its child welfare toolbox, BJ says. “I think Safe Families is a lever to help us get to a place where preventing child abuse and neglect is as much the game as investigating abuse and neglect and putting kids in foster care.”

And it’s possible to win that support more often and sooner in the process, but relationship building needs to take precedence, Ken shares. Collaboration across key sectors with a commitment to the same north star is what will drive progress more quickly. Focusing on what principles are agreed upon and understanding how to help one another in the process makes all the difference.

“I think bringing in the church, business leaders, political leaders, state and federal representatives makes it so that our voice doesn’t feel like a program being instantly created and you better jump on board. I mean it’s just relationships. That’s all it is.”

Ken Norwood

Even though the organization experienced some hurdles, Safe Families has proven that the model is scalable – and necessary. And the COVID-19 pandemic is only further shedding light on this need. Safe Families has seen a surge in demand for its services in the Midwest in particular. Department of Children and Family Services directors are repeatedly calling on Safe Families to take on more youth.

Crises such as unexpected job loss, health issues, and social isolation lead to neglect, abuse, and violent incidents within families. Add in stressors such as increased difficulty in accessing food and other products, little to no access to transportation, and cancellation of in-person visits for those already involved with the system, and you have a toxic cocktail of outcomes for extremely vulnerable children and their families who will be looking to Safe Families for support.

Looking ahead, the pressing need to expand into Florida is where Safe Families will aim a lot of its focus. Florida has the third highest foster care population and Safe Families’ presence there remains minimal. Success in Florida through a coalition of partnerships with churches, civil society groups, and the state’s Department of Family and Children’s Services will serve as a blueprint for this kind of expansion nationwide.

Forever strengthened

The relationships formed through Safe Families have transformative effects on both families. In foster care, sometimes the parents find it difficult to move back from the edge of the cliff because their support system is not expanding. Their social workers check in on them when they can, but the parents are paralyzed by the thought of the state taking custody of their kids.

“Ironically, that ain’t happening a whole lot in Safe Families,” BJ Walker points out. “There’s something … about this relationship that forms that does have a residual effect on the parent. These are not parents who, ‘Everything is good. I’m fine. I just want to drop the kids off.’ These are parents that are having a genuine crisis or struggle, so I can’t help but think, ‘Hmm, there must be something about that relationship that’s redeeming to them.’”

And it’s paradigm shifting for host families. “It levels the playing field,” Nicole says. “You start to have contact with others that are different than you, that have different backgrounds, that have different life experiences. You no longer just see them as an ‘other,’ but you see them as a person that you love and care about because you’re in a relationship with them.”

This can be the Family Coach, for example, helping parents make a plan for achieving their goals and checking in to ensure they’re on track. Or once the placement is finished and the family is together again and no longer in crisis, this can be the host family or a Family Friend checking in to see how the parents are doing, asking if they need anything, offering to watch the kids to give the parents a break.

For a kid in a crisis situation, explains Joyce, rather than experiencing the trauma of being forcibly removed from his home, that kid sees his mom making plans with another mom to take care of him for a while, a totally normal occurrence, and then he sees and talks to her regularly while with this other family.

“Most families that are struggling are isolated, disconnected from people who are not struggling, and so they don’t have a resource or a model of what it looks like to consistently not struggle.”

BJ Walker

Nicole agrees: “They need relationships with people who are outside of poverty and, when I say poverty, it’s every kind of poverty, emotional, spiritual, social, and physical. Many of those families that I worked with were isolated in some regard or another.” Safe Families brings kids and their parents into those positive relationships and gives them the opportunity to experience a different way of life, a healthy way of doing family.

Joyce tells a story of dropping a container of yogurt while hosting a little boy. As she was gathering towels to clean it up, the garage door opened, signaling the arrival of Joyce’s husband. The boy visibly tensed. He was clearly petrified. Joyce’s husband walked in, commented on the mess like the trivial matter it was, and joined in the cleanup. The boy relaxed, and Joyce realized he assumed her husband would be angry about the incident and react violently. That had been his experience so far in life. Joyce and her husband were able to give that boy a small glimpse into another way of handling life’s minor annoyances.

“I’m giving a child who’s tasted trauma, like few people ever will, a seat at my table to think, to dream, to build, to write,” says Ken. “I mean, we’re giving them exposure into normalcy, as normal as any family can be. That will totally change their trajectory for life.”

“The hope of the home and the redemption of a parent and the model of a family is our greatest hope, and that’s what we do every day. And we do it better than anybody.”

Ken Norwood

Learn More About Our Efforts in Economic Progress

Photography by David Johnson