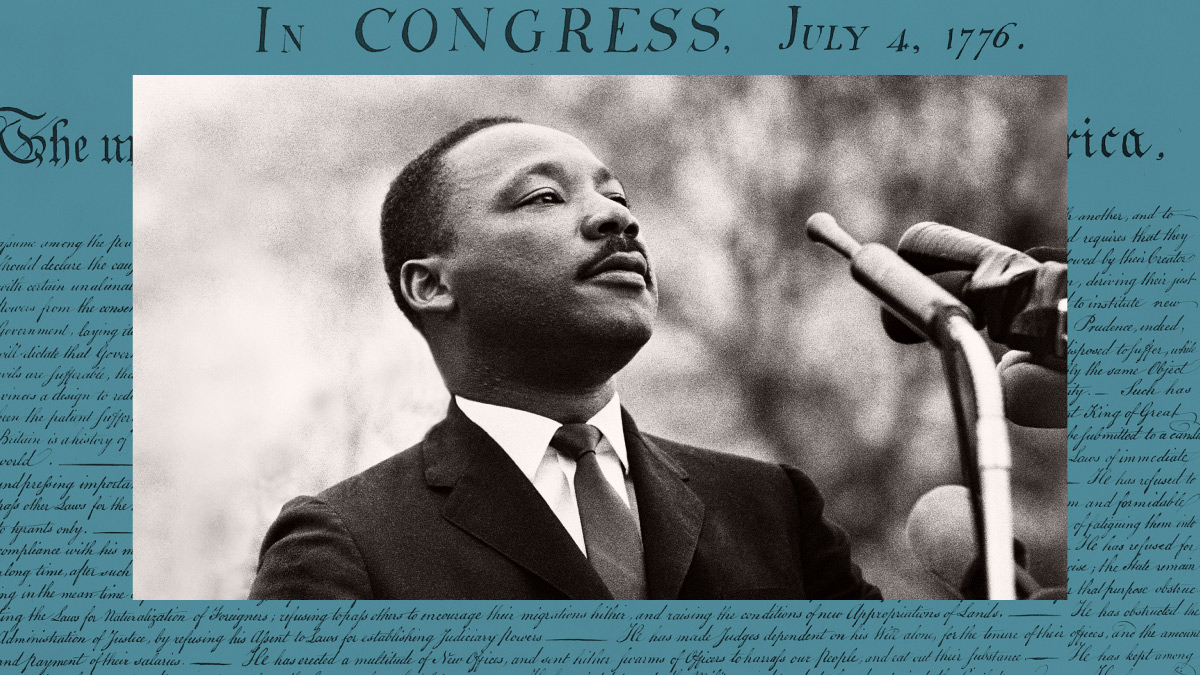

Why Martin Luther King Jr.’s message is more vital than ever

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s message wasn’t particularly groundbreaking, according to Pastor and Community Leader Dr. DeForest “Buster” Soaries. Not only does it predate King all the way to America’s founding promise, but it’s also just as needed today as it was in the Civil Rights era.

Dr. King did not envision himself as having any unique ideas,” says Dr. Soaries, who spent over three decades as the Senior Pastor at the First Baptist Church of Lincoln Gardens in New Jersey and is a leader in faith-based community development, economic empowerment, and financial freedom. “But based on [King’s] understanding of the American promise, the Declaration of Independence, the principles of the Founders, this self-evident truth that all humans were created equal, Dr. King said that what he was attempting to do was to help America be true to what America said about America on paper.”

The day Dr. King was assassinated in 1968, Dr. Soaries set out on a years-long trajectory that would see him move to the forefront of continuing Dr. King’s legacy, working tirelessly as a Baptist pastor, community organizer, and the first African American male Secretary of State of New Jersey. He rode shotgun with white police officers during the 1990s race riots in New Brunswick, wrote 12 books, and helped implement the 2002 “Help America Vote Act.” In 2005, Dr. Soaries founded a Stand Together Foundation Catalyst, the dfree Financial Freedom Movement, which has helped many people become financially self-sufficient.

Soaries doesn’t see Martin Luther King Jr.’s message as a relic of history that applied only to its time. He sees it as an ongoing effort that each and every person in America plays a role in actively upholding. Ahead of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Dr. Soaries answers some questions about how to interpret Dr. King’s message more than 50 years later, and how everyday people can continue to advance the principles of human dignity and equal rights in their communities.

Stand Together: When it comes to Civil Rights, what has changed, and what has stayed the same?

Dr. Soaries: Human nature basically doesn’t change. Love and family and camaraderie and friendship, the connection that we have to each other emotionally and spiritually, all of those things have existed throughout humankind. Hatred and war, resentment, jealousy, and envy — those sentiments and feelings have also manifested themselves for all of humanity.

What happens in a civilized society is that humans evolve in such a way as to create institutions that seek to foster the good and limit the bad. In that sense, there have always been people who felt superior to others, but institutionally we’ve been able to address the manifestation of those kinds of feelings by dismantling systems like slavery. So while I may feel that I’m superior to someone else, I’m restricted institutionally from manifesting that feeling by holding them hostage and owning them as property. I think what you’re getting at is, do I think human nature has changed? No, I don’t think human nature has changed at all.

Today, because of technological advances, people and their voices can travel faster and farther than they could 250 or even 50 years ago. That means ideas — both the good and the bad — can reach and shape our communities and our country on a scale we’re still appreciating.

Americans today have the opportunity to find ways to apply and advance our principles in this emerging media environment. It can feel daunting. But the potential is limitless if we have the courage to protect the very principles that made it possible for these advances to flourish.

How can people take more effective action toward progress?

Dr. King was not only a leader of nonviolent protest. He was a proponent of the principles of nonviolence. So when you look at Martin Luther King Jr., you normally see only two things: you see a leader in equality, civil rights, and justice. You also see a charismatic leader of a nonviolent social protest. But I think more of us should focus on the third aspect of Dr. King, and that is a proponent of nonviolence as a lifestyle.

The first principle of nonviolence is that it seeks to win friendship. The goal for Dr. King was what he called this Beloved Community, and for Dr. King, the second principle of nonviolence was redemption and reconciliation. Dr. King was not simply focused on winning a campaign as much as he was winning people over to a lifestyle.

As Martin Luther King Jr. Day approaches, is there a particular memory forefront in your mind?

I served a congregation in central New Jersey for about 30 years as a Black Baptist preacher. The image of King and the model of King loomed large over my persona in my profession, as it does every Black Baptist preacher. I would argue the question every Black preacher has had to answer since 1968 is, “To what extent am I adding to the King legacy?”

I led a congregation that became very large under my leadership. We had a very diverse community, and on three or four occasions, we had the unfortunate instance of a young unarmed Black male being killed by a white police officer. Fortunately, we had public officials who were more responsive than they had been in other areas.

About halfway through my tenure, we had a gas station that was owned by Indian immigrants, and it was robbed by a young African-American. During the robbery, the young Black man killed the owner of the gas station.

That Sunday, I announced in church that when we ended our worship we were going to have a march. Our congregation was going to march from the church to the gas station and have a rally to declare our support for the family of the Indian man who was shot. My thesis was that had a white person shot and killed a Black person, as a Black church, we would be responding in kind. I wanted to make sure that we were morally consistent in being just as angry about a Black person shooting an Indian immigrant as we would be a white person, particularly a white policeman, shooting a young Black unarmed assailant.

I hope that it was a very impressive event for the people in our congregation, especially young people. I wanted to send the message that moral consistency was a requirement for people who were advocates for civil rights and people who saw themselves as promoters of justice. Of all the things we did, and we did a lot of things — I mean we built houses, adopted foster children — I think that one incident, that one event stands out in my mind as being probably the most like Martin Luther King Jr. of my career.

What is the most relevant insight we should carry forward from Dr. King’s message and approach to social change?

We often measure civil rights in terms of legal victories, in terms of the rights to practice certain behaviors, when in fact Dr. King’s vision was much broader than that. It was much deeper than that. When he talked about the children of slaves sitting down at the table with the children of slave masters, that was a metaphor for the Beloved Community. He was talking about the Beloved Community. That was King’s dream and hope, that America would become a family.

When you look at the country, for almost 250 years now we’ve been able to self-correct as we aspired to the lofty ideals described in those principles [e.g., freedom of speech, freedom of the press, equal representation under the law]. That’s really the genius of America. It was founded by principles that required continuous investment in “the more perfect union.” It’s the idea that perfection would not be attained, but would be sought. So America really is an experiment in civil society that seeks to become better, rather than perfecting the art of being what it is.

Dr. King’s vision of the Beloved Community aligned with his religious convictions and his commitment to the founding principles of America. He believed in the American stated ideals of equality and opportunity. Therefore, his fight for justice was his way of helping America become a nation whose reality was consistent with its rhetoric. Achieving that goal requires Americans who will exercise radical empathy, appreciate free speech, and who will participate in “no blame” dialog that seeks common ground and mutual endeavor.